The interventions of Afrikaans poets on the work of Hieronymous Bosch

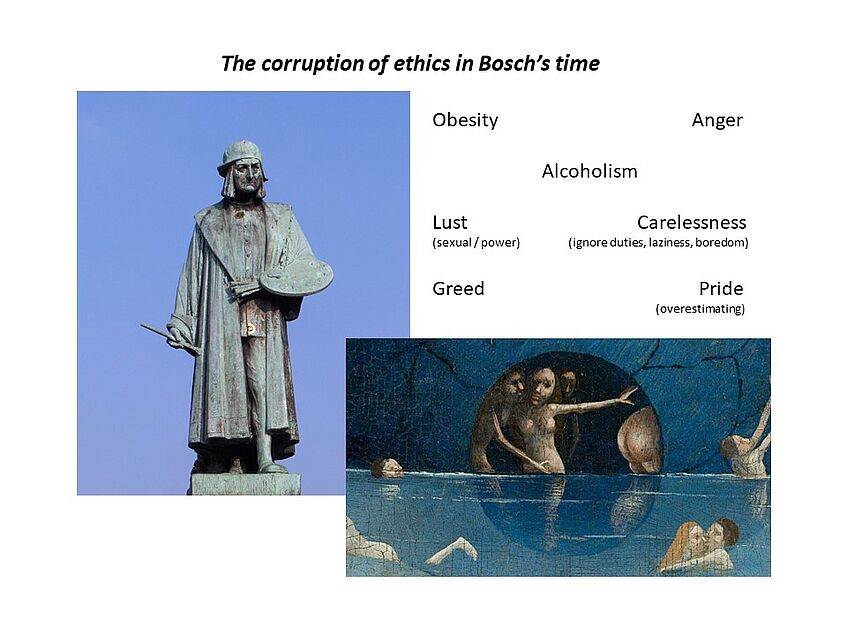

´n Portret van Jeroen Bosch

´n Gravuur op koper (1572)

Thank you for the opportunity to share a few thoughts on the paintings of Hieronymus Bosch and the interventions of Afrikaans poets on his work – primarily on The Garden of Earthly Delights, more or less from 1503.

Life and times of Bosch

Hieronymus Bosch was born in 1450 in ’s Hertogenbosch, shortened to Den Bosch for the rest of this lecture. Despite his international fame as a painter of strange and timeless creatures, he was closely related to this city for his whole life. Bosch is born as Hieronymus van Aken from a family of painters. He changed his last name to fit to his daily living space. The grandfather of Bosch, Johannes Thomas van Aken, was the initiator of the Van Aken Workshop in their new city. He had five sons and they all became painters: Thomas the eldest, then Johannes, Hubert and Goessen with the youngest son Antonius as the father of our timeless hero, Hieronymus. The Van Aken grandfather was the most important painter in Den Bosch in the first half of the 15th century.

In the year 1430 he and his wife became members of the well-established Brotherhood of Our Lady of Den Bosch. This brotherhood was a strong body of cooperation between the religious, economic and political elite of the city. In the Cathedral of St. John, the most important church of Den Bosch, you can even today see a fresco at the back side of the choir that leads back to the Van Aken Workshop. This painting, the Crucifixion with Donors dated 1453 to 1454, became the example Bosch used for his first commissioned work. He painted Calvary with Donors between 1485 and 1490.

The Van Aken dynasty became famous. All the family members lived a good life with enough money, prestige and special privileges. Bosch’s family lived on the east side of the central market. Bosch was the fourth of five children. He had two brothers and two sisters, but almost nothing further is known about the first twenty year of his life, except that he matriculated at a Latin School – a school that prepares the learners for university. What we can see of his youth in many of his paintings is the big fire that destroyed the city on the 13th of June 1463. Bosch was then 13 years old. Four thousand wooden houses burned to ashes. Inferno! What Bosch saw and experienced occurs as hell painted on the right side panels of many of his triptychs.

We don’t know if Bosch traveled through Europe as a young painter. Travelling was custom to get some experience and learn new techniques, but it was not yet customary as it became later. We also don’t know if he had any education after his schoolyears. An important factor in his life was his marriage to Aleid van der Mervenne, the daughter of a rich merchant (businessman / tradesman) and patrician. Bosch sold his share in his parent’s house to his brother Goessen and left to go and live with his wife, who was from an even higher social status. He opened his own workshop. From that moment he became an independent painter. While his own family had some financial worries, Bosch was now the receiver of big sums of money and the collector of some pay-in-kind, meaning payments in services and products. His wife Aleid also inherited the estate Ten Roedeken from her brother Goyaert. It was twenty five kilometers south from Den Bosch. The couple used it for an extra income. Bosch received the usufruct (vruggebruik) of Ten Roedeken. Bosch himself also became member of the Brotherhood of Our Lady: firstly on the basis of his properties and secondly on his privileged spiritual position in the Catholic Church. Bosh was the only painter in this brotherhood of academics, medical doctors and lawyers. He was very successful, part of the elite in his city and he knew how to convince his commissioners of his talent. The German art historian Nils Büttner wrote about Bosch’s activities in this old boy’s network and the member’s respect for his knowledge of religion despite his image of painter of the devil. Bosch died in 1516.

In 2017 the Netherlands and Spain celebrated his work – 500 years after his death – with two big exhibitions:

- Jheronimus Bosch, Visioenen van een genie in the North Brabant Museum in Den Bosch and

- El Bosco, La exposición del V Centenario in the Prado Museum in Madrid.

Bosch lived during the late Gothic, early Renaissance period. All the fellow painters of Bosch painted harmonious, beautiful work, mostly commissioned work for the church. His contemporary, the humanist, poet and painter Dominicus Lampsonius wrote the following about painters during the Renaissance and specifically about Bosch as part of a portrait gallery by Volcxken Diercks:

“A beautiful human being makes beautiful paintings.

A bad tempered, pessimistic human being makes dark, disharmonic paintings.

Even the monsters and the hell in Bosch’s paintings look very real, because he painted them after he probably saw them in the underworld.

Hieronymus Bosch, what secret covers your fascinating, almost expressionless sight? Why is your face so pale?”

The authentic thing about the paintings of Bosch was not the religious content, but the detailed combination of dream images with nightmares, hell and damnation that turned the medieval perspective of what good paintings are upside down. Gone was the churchly peace! Bosch used satire, grotesque and parody. He challenged the viewers in his world to do some introspection into the corruption of their own ethics:

- Obesity

- Alcoholism

- Lust (sexual or lust for power)

- Greed (a longing for food or status)

- Anger

- Pride (the negative sense of a foolish, self over rated sense of one's own personal value, status or accomplishments) and

- Carelessness

(Concerning the self, the other and duties – a state of mind that gives rise to boredom, apathy and laziness).

Does it sound familiar?

Even today, at the beginning of the 21 century, does Bosch’s reflection on our morals still work as a mirror? If your answer is YES, then you already understand more than half of this lecture today!

Bosch had a very detailed knowledge of Bible texts, the life of saints and symbolic meanings of the animals during his time. He combined this knowledge to produce unique iconography. His paintings are moralistic.

Bosch gave visionary imagery to words that only existed in literary texts at that time: satire, grotesque, parody. He translated these words into images. In the literary world we call it ekphrasis. It is a Greek word for the description of a work of art produced as a rhetorical exercise. But Bosch did the opposite: from words on paper to paint on wood like the description of the shield of Achilles in the Iliad. First were Homer’s words. Then there were the paintings. Ekphrastic poems (like the Iliad) provide detailed descriptions. Some painters, like the Italian Angelo Monticelli (from the turn of the 18th century) tried to paint an interpretation of the shield of Achilles by using the description of Homer from the 8th century BC. Between the description and painting lay 1000 years. Bosch did the same with literary concepts like satire etc. Four to five hundred years after the death of Bosch Afrikaans poets wrote ekphrastic poems on two of his most known paintings:

- Garden of Earthly Delights (painted between 1495

- and 1505)The Hay Wain (painted in 1516)

Oeuvre in Vienna (and elsewhere)

The oeuvre of Bosch consists of more or less 27 paintings and two dozen sketches. Almost a third of his paintings are triptychs as altarpieces – all of them crowded with people, animals, plants and scary creatures – mostly in settings from paradise to hell.

Here in Vienna you have the privilege to enjoy the triptych The Last Judgement at the Academy of Fine Arts. This painting is painted between the year 1500 and 1505 with an overlaps in time concerning The Garden of Earthly Delights. The Last Judgement is still in a very good condition after more than 500 years. No Afrikaans poet wrote an ekphrastic poem on it.

As already mentioned, the first commissioned work of Bosch was Calvary with Donors. He was thirty five years old. It was custom during those days to use an already existing painting as an example for a new interpretation. He used a painting from one of his family members from the Van Aken Workshop. Also customary to his time, he painted all the faces in the same way – flat – except the face of his commissioner. The commissioner’s face has more character.

The most outstanding and famous triptych of Bosch is the Garden of Earthly Delights. It consists of three panels on the inside:

1. on the left: paradise or The Garden of Eden

2. in the middle: life on earth with all its temptations

3. and on the right: hell or The Last Judgement.

The two outside panels of this painting are not important in the context of this lecture.

Since 1936 The Garden of Earthly Delights belongs to Museum Prado in Madrid.

The painting was first witnessed in a castle of Count Henry III of Nassau-Dillenburg-Dietz in Brussels.

Secondly it was inherited by William the Silent – Prince of Orange.

Thirdly it was confiscated by the Duke of Alva in 1568 and carried by his servants mostly on foot from the Low Lands to the north of Spain – an impressive journey for such a big and important painting.

Fourthly is was passed over to Duke Don Fernando, bastard son to Alva.

Lastly king Fillips II of Spain bought it and took it to his monastery palace, El Escorial, fifty kilometers north of Madrid. For the Spanish Bosch became El Bosco. It is not only a painting crowded with biblical meanings and symbolic acts. It is also a painting with an impressive history divided between the Netherlands and Belgium in the north of Europe and Spain in the south of Europe.

Hallmark Europe!

This painting was noticed by Afrikaans poets while visiting the Netherlands and Belgium.

Another painting receiving attention by South African poets is The Hay Wain Triptych. It is also the property of Museum Prado in Madrid. The Hay Wain was painted in 1516. It has the same division as The Garden of Earthly Delights:

- on the left side: paradise or The Garden of Eden, but now highly infected with the fall of man

- in the middle: life with all its sins like lust, greed, anger and pride on an overloaded hay wain

- and on the right side: hell or The Last Judgement as the end destination of this hay wain

The story is the same, but the playfulness of The Garden of Earthly Delights is gone now. Even the swallows in the left upper corner of this painting became insects and small insect like men falling from heaven. The story of Adam and Eve in this so called paradise on the left is a narrative about carelessness, temptation and exile of Adam and Eve from the Garden of Eden. In the middle the hay wain is followed by the rich and important, kings and statesmen – all longing for MORE and MORE – and pulled by the poor, animal like men and monsters. There is no playful temptation on earth anymore. On the right side you can again see wounded men, a woman with a frog between her legs and a big fire in the background just like in The Garden of Earthly Delights.

These two paintings where the source of inspiration for the Afrikaans poets Dirk J Opperman, W.E.G. Louw, Antjie Krog, Marlene van Niekerk and Johan van Wyk. None of these connections between painting and poem are obvious. Why did it happen? How did it happen? Like Shakespeare once proclaimed in Hamlet: “There are more things in heaven and on earth, Horatio, than are dreamt of in your philosophy.” Another two Afrikaans poets wrote work that strongly connected to The Garden of Earthly Delights, maybe without even knowing it. They are Heilna du Plooy and Charl-Pierre Naudé. The analytical psychologist Carl Gustav Jung called it synchronicity for the first time. Synchronicity is a concept which holds that events or works of art are “meaningful coincidences” if they occur with no causal relationship. This concept was influential in the world of literature. Later on theorists rejected it. Still. It reoccurs from time to time and can serve a purpose.

Short cut through life in Afrikaans South Africa

What was life like in South Africa during the 20th century? Especially, what was it like for Afrikaans speaking people? Did they feel guilty of corrupting of their own ethics?

WAR AND OPPRESSION

At the start there was a war going on against the British, the colonial oppressor.

The Second Freedom War lasted three years at the turn of the century from 1899 to 1902.

The Afrikaner-Boers lost the war after the enforcement of the "scorched earth" policy by the British – meaning burning down the farms, houses and crops of the farmers.

The British learned the guerilla fighting technique form the Boer (as they had learned in their turn from Shaka, the king of the Zulus).

The Boers experienced the controlling forces of concentration camps for women, children and elderly from the British.

Afrikaans, the language of the Boer, was banned.

English English everything English

In our schools and in our churches

Our mother tongue gets killed

Both sides (Boer and British) used their new skills during the rest of the 20th century in wars and in townships against blacks. But to win the cooperation of the Afrikaner Boers in South Africa, the British Empire did two big things right. They promised:

- to keep their hands off the church and

- hands off Afrikaans, the language of the Boers that originated from Dutch.

OFFICIAL STATUS

Afrikaans received official status from the British government in 1925 – an official status shared with English.

PRIDE

Afrikaans became more and more a white language. In the heyday of Apartheid Afrikaans officially turned fifty years old. It was 1975 and the occasion was celebrated with a Language Monument on top of the Paarl mountain overlooking the heartland of Afrikaans. Spot on? Misplaced?

OPPRESSOR AND OVERESTIMATION

Prime Minister Hendrik Verwoerd planted the first seeds for Apartheid in 1948, calling it segregation. He was the mastermind of the oppression of racial segregation and discrimination in the name of Apartheid. He was Dutch and born in Amsterdam.

The position of Afrikaans became vulnerable.

Once oppressed by the older and much bigger language English, the younger language Afrikaans now became the new oppressor under the ideology of Apartheid.

When Afrikaans was forced down on black leaners in the townships hell was loose in the streets of Soweto. The 12 year old Hector Peterson was shot down on the 16th of June 1976 during the Soweto uprising. The sixty’s and seventies were revolting times in South Africa.

DOWNFALL

Apartheid ended in 1994. Victory for democracy. Disaster for the Afrikaans speaking Afrikaner or so called Boer. Afrikaans as the second official language tumbled from its pedestal. It became a language among other languages in South Africa. A political decision based on equal rights in a democratic South Africa. All the established positions of Afrikaans as a language in the administration of justice, in the medical world and in education started to crumble.

Many poets who wrote against Apartheid thought there was nothing left to write about.

SUFFERING

At the turn of the century it looked like Afrikaans was doomed to be listed as an endangered language. Statistically colloured speakers come to the rescue of Afrikaans. There are still few poets among this group despite Adam Small, Peter Snyders, Ronelda Kamfer, Nathan Trantaal and some others. Afrikaans is the third biggest language in South Africa.

ALL THIS shaped South Africa and its Afrikaans poets in the 20th century.

What poets do with paintings

Let us follow the history line of Afrikaans poetry connecting some poems to the paintings of Bosch.

JEROEN BOSCH

The world is vain but my spirit is vainer,

curing some thirty nights' nightmares

of thorny plants, birds, and people.

From regions of the earth, old and new, the devil

chooses ever more lustily costumes and masks

for me, for you, for thousands upon thousands.

It hauls cortèges, fêtes around the Cross, changing

shape through the centuries; but the game

remains the same in monks, machines, or thill.

And caught eternally in the cycle of desire

we ride, spurring the stallions’ flanks

round and round the crows on naked women in the dam.

O Beloved! Come then, let us flee from the revels

sheltering in mussel, horny husk – and far above

the carnival of evil floating in glass bubbles.

Because the dunce is in me, the fish-lipped fool

whistles at the magician’s every trick

but mocks miracles and His crucifixion;

and if I summon God and Anthony together

he is already there who from a new rankness

farts the first swallows recklessly through a funnel.

D J Opperman

translation: Gisela and Tony Ullyatt

Opperman wrote this poem as a summary of Bosch’s works and the shared zeitgeist between himself and Bosch. A zeitgeist they both appropriated. Both of them accepted their tasks as evangelists, as prophets against the apocalypse. They warned against evil, the wandering devil that gives us strange outfits and masks to follow him on earth. Bosch and Opperman used their painting and poem to criticize the ethics of their own world. Listen again to the 1 verse:

The world is vain but my spirit is vainer,

curing some thirty nights' nightmares

of thorny plants, birds, and people.

and take notice of the words in verse 2:

… the devil

chooses ever more lustily costumes and masks

for me, for you…

These verses can fit in all three of the mentioned triptychs of Bosch. But in verse 4 your sight is forced to focus on the middle of The Garden of Earthly Delights. Opperman describes a Morris dance (in German Moriskentanz) or fertility ritual from the medieval 15th century. This circuit of lust shows men on horses, camels, bulls, bears, unicorns and so forth circling bathing women. They’re carrying fruits, eggs, fish and birds, perhaps as presents to the women.

And caught eternally in the cycle of desire

we ride, spurring the stallions’ flanks

round and round the crows on naked women in the dam.

There is full appropriation of Opperman with the evil in his poem as it is painted by Bosch. The pessimistic second phase in Opperman’s oeuvre is reflected reflects here in his ekphrastic poem. Images of strange lipped fishes occur also on more panels in Bosch’s triptych The Temptation of Saint Anthony. Opperman claims this painting in his last verse to come back once more to the right panel – the hell in The Garden with Earthly Delights.

and if I summon God and Anthony together

he is already there who from a new rankness

farts the first swallows recklessly through a funnel.

Triptych: the garden of earthly delights

The lute-player sits pinned against his lute –

a butcher bird’s corn cricket on a twig!

The strings of the harp are strung right through

the harp-player, so that he hangs – as if crucified.

(lines 42 – 45)

Further-on the devil, Modikak, sits on his “throne”

a chamber pot his crown, his feet in urns:

with his beak he devours his victims one by one.

Through blue membranous intestines one falls

into a sewerage pit; a miser squats over the side

and stealthily drops his turds on golden ducates.

But a love tent is adorned with curtains draped

around this high chair; coiffed whores are peeping

on the love games of a man and a frog;

a vain woman sees herself and an ass – her lover –

reflected in a mirror on the backside of a devil.

(lines 56 – 66)

W.E.G. Louw

translation: Heilna du Plooy

The two extracts describe a specific eye catching part in the hell of The Garden of Earthly Delights. As opposed to Opperman, Louw focuses on just this one painting. This detailed description and summary between lines 56 and 66 gives away more about Louw, his knowledge of European literature and one of the customs in the South African culture. Let us focus on the first 2 lines:

Further-on the devil, Modikak, sits on his “throne”

a chamber pot his crown, his feet in urns:

Afrikaans differs a lot from Dutch in the habit of name giving to their loved ones. Maybe this young language took after the language of her previous colonial oppressor? It is no coincidence that the words of Juliet in Shakespeare’s Romeo and Juliet echo in Afrikaans speakers harts.

“What’s in a name?”

The name “Modikak” is used satirically meaning something like king of shit in times when every value was lost and turned into secretion. This brutal reference to poop, shit and secretion is not English at all and it is very hard on the Afrikaans ear, but it is recognizable in the Dutch culture. Louw must have identified this phenomenon on his visits to the Low Lands together with The Garden of Earthly Delights. But it goes further. Louw was a well-read man. The creation of a name like “Modikak” may also connect to a play of the young French author Alfred Jarry called King Ubu, first performed in Paris in 1896. It was a bizarre play and significant for the way it overturns cultural rules, norms and conventions. The Irish poet Yeats was in the audience. He recognized King Ubu as an important happening. Afterwards it seemed to be the opening door to Modernism in the 20th century. King Ubu was the predecessor of Dada, Surrealism and the Theatre of the Absurd. Jarry was 23 years old. He satirizes greed and power, because Ubu is a French nonsense word evolving from the French pronunciation of the name "Herbert" – one of his ex-teachers. The word “uburlesque” became part of the European literary world. Louw used the concept of the “uburlesque” in his poem.

A second connection to The Netherlands you can find in the word “throne” for toilet. It is part of the Dutch culture and was implanted in the Afrikaans world. On the head of “Modikak” Bosch painted a pot that I recognize as a three-legged cast iron African pot. The blacks traditionally use it for cooking on fire. It also became a favorite tool for whites in their barbeque tradition – to make “potjiekos”. Louw translated the image of this pot to the word “penspotjie”. The image is very familiar in African culture. Bosch could not have known the African connection he made in his painting. The pot must have other meanings and uses in those days.

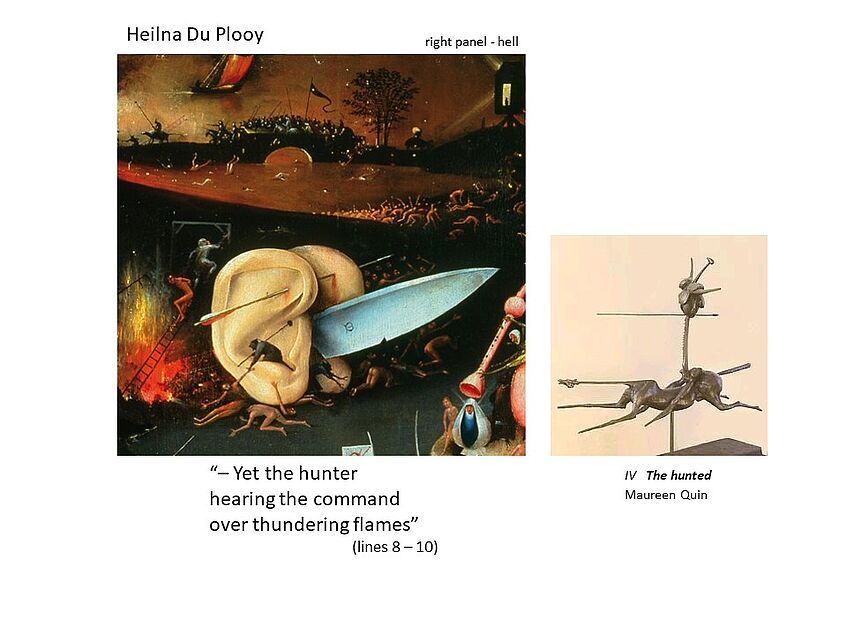

The Hunt

In conversation with the series of sculptures, The Hunt, by Maureen Quin

IV

the hunted

scorched

by the heat of the battle

deafened

by the sound of death

among swords and horses

canons and guns

airplanes and missiles

– yet the hunter

hearing the command

over thundering flames

through consuming roars

again and again

pulls back his bow,

aiming his arrow

accurately

at the chest

in the heart

of any

one

on

the

other

side

whose arms fly out

even before he falls

and calls

up high down low

from whence cometh

no help at all

and in this din

of degeneration

the only heartrending

cry of anguish

plunges from the horse’s

strained mouth

Heilna du Plooy

translation: the poet

The Hunt is also an ekphrastic poem, but it is not a description on work of Bosch in the first place. It is written as a conversation piece in seven parts on a series of bronze sculptures by Maureen Quin and an appropriation and poetical interpretation of this work of Quin.

While reading this poem we experience a growing meaningful coincidence with The Garden of Earthly Delights, especially part 4 the hunted. It is certainly a matter of Jung’s synchronicity (German: Synchronizität). The hunted is not only an animal, but also the human being hunted down by its own species during wartime. Lines 2 – 8:

scorched

by the heat of the battle

deafened

by the sound of death

among swords and horses

canons and guns

airplanes and missiles

Hunt also occurs in the hell of The Garden of Earthly Delights where human beings are hunted by their friends and by their own pets or small animals like dogs, mice, rabbits, swallows etc. Bosch’s hell is full of swords and knifes and the skull of a horse. In lines 10 – 20 a fire is destroying a city in the background, the fire of Bosch’s youth.

hearing the command

over thundering flames

through consuming roars

At the end of part 4 Du Plooy describes the sounds escaping from a dying horse. It is an earlier stage of the skull as Bosch painted it. Du Plooy’s dying horse also reminds us of the horse on the Guernica of Pablo Picasso.

the only heartrending

cry of anguish

plunges from the horse’s

strained mouth

Quin. Bosch. Picasso. The ekphrastic part 4 of this poem is embedded in the art history of the world. This whole seven parted poem is a very strong warning against killings and wars and evil, like Bosch also meant in his painting.

In the next two poems we are back in the middle panel of The Garden of Earthly Delights with all its lust, playfulness and temptations. The female poets Antjie Krog and her poem BOKKIE ( 1970) in combination with Marlene van Niekerk and her poem GARDEN OF EARTHLY DELIGHTS (1977) come along. The connection to Bosch in Van Niekerk’s poem is obvious. Both poets appropriated the content of desire. Both poets transferred the space in Bosch’s painting to a South African environment. In Krogs poem the connection is less obvious. It looks like a poem about flowers (wisteria, evening flower and jasmine), about harp music and about making love all the way up to the orgasm.

BOKKIE

My Bokkie you and I

lay down in the swamp

to make love between wild reed.

Your body is like a brown violin

stretched to get some resin.

There´s wisteria in your eyes

evening flower in your hair

and from your navel vide truly

white jasmine.

I cut your mouth and drink your juice

and cry when wisteria tap from your eyes.

I bruise the flowers in your hair

break your finely tuned strings

and cry out loud when I chop you up.

Antjie Krog

translation: Carina vd Walt & Geno Spoormans

Do you remember the words “What’s in a name?” from Juliet. BOKKIE is a South African pet name for your loved one. BOKKIE means "little buck" or "doe" – the diminutive of the Afrikaans word “bok”. It is in both Afrikaans and English a popular term of endearment, comparable to "sweetheart" or "honey”. If you look very closely to the middle of the panel in Bosch’s garden you can see a buck sniffing a man. Without this image and the name BOKKIE the connection is almost not possible. Krog moved from nature to culture in 5 lines.

My Bokkie you and I

lay down in the moor

to make love between wild reed.

Your body is like a brown violin

stretched to get some resin.

All music outside the church was suspicious during medieval times. Music was dangerous. People believed it leads to dances and seduction, like the Morris dance on the other side of the fountain in Bosch’s painting. And indeed! In this poem lovemaking is dangerously serious stuff, going all the way until the strings of the violin snap. Little death in lines 12 to 14. La petite mort.

I bruise the flowers in your hair

snap your finely tuned strings

and cry out loud as I do you down.

Marlene van Niekerk wrote the short story Die vrou wat haar verkyker vergeet het (The woman who forgot her binoculars). The most crowded part in the middle panel of The Garden of Earthly Delights reminds us of that woman in the story, who made the birds in her garden eat her own flesh, drink her blood – note the Christian reference. But Van Niekerk does not take it to this extend in her poem GARDEN OF EARTHLY DELIGHTS. (Unfortunately this poem is not translated in English.) She doesn’t go all the way in her lovemaking. She has a scattered mind, is easily distract by the wild goose.

In her poem words like the following are common names of South African plants: Cape snow bush, bell-heath, marigold, Livingstone daisy and chincherinchee. The wild goose catches silver fish, while the lover tries to keep her attention to the act of love making. Therefor she calls her beloved in her poem by various pet names:

· jantjieberend

· bokgousblom (prefix “bok” + marigold)

· beesbulletjie

For the third time the same question appears: “What’s in a name?” In South Africa there’s a whole lot in a name! And it reminds us of BOKKIE.

The three occurrences of ‘you and I in GARDEN OF EARTHLY DELIGHTS become familiar. And last, but not least: the violin of Krog reappears in line 15 of this poem of Van Niekerk. A violin with its high sounds compared to the sound the stems of a chincherinchee make when rubbing together in the wind.

The pet names, the repetitions and the violin lead to two possible conclusions: GARDEN OF EARTHLY DELIGHTS is a matter of synchronicity or a matter of a graft to BOKKIE. But if there was any doubt about the origin of Krogs poem it is gone now.

The last two poems in this lecture do not refer to The Garden of Earthly Delights, but to The Hay Wain. The Afrikaans poet Johan van Wyk describes this triptych of Bosch with the poem hieronymus bosch’s haywain.

hieronymus bosch’s haywain

the rebellious insects swimming away in an arc

to the virgin rock, a market woman

between fruit trees, God marrying

adam and eve, renegades are banned

to the earth the paradise

while they fall

look at them with flashing eyes looking at the woman, naked

and stupid, “that pain exists is necessary lord”

God’s advisor bites him on the ear,

“may we give them knowledge

it’s democratic lord, may they naked

pluck each other’s fruit

and quickly try to cover up their ardour with begging

hands, leaves and rags, may they have pain,

lord, and together may they collapse

in the dust, punish us thus, lord”

the sad angel with the sword

hunts them out, still with fear and sleep

in their eyes, so it happened that everyone

followed the haywain: the nuns who filled the fat monk’s pockets

with corn, a brother who slit his brother’s

throat, ministers with political commentators

following decently and gluttons perishing under the wheel

a crowd of beasts goading humankind to hell

it’s every man for himself, by himself

even sex is only for self, the spouse

broken in after the love transaction

and “ena gives advice” psychobabbling about what

we should make of problems

every dynast is an antichrist who cares for

his people’s needs, ensuring that the wain of discord

never gets out of sight and no one

except an angle looks up to God

on a cloud above all the Turmoil, in hell

everyone is afraid he will be raped or tortured no longer

because that pain exists is necessary

Johan van Wyk

translation: Gisela & Tony Ullyatt

Van Wyk started at the left panel describing the fall of man with the words “rebellious insects” (line 1) and banned “renegades” (line 4). The poet also puts the woman in a bad position in count of her nakedness and stupidity. He stated a meaning in inverted comma’s in line 9 about the necessity of pain to serve God:

while they fall

look at them with flashing eyes looking at the woman, naked

and stupid, “that pain exists is necessary lord”

The citation in this line is a literary hint. It is an intertextual reaction on the line “that pain exists is unnecessary Lord” in Breytenbach’s poem breyten bid vir homself. The relatively unknown poet Gert Strydom also used the line “that pain exists is necessary” in response to Breytenbachs words. Breytenbach wrote this line back in history as a response to “that pain exists is necessary Lord” from N.P. van Wyk Louw in his poem Ignatius bid vir himself. Van Wyk is turning the line back again to its origin. Breytenbachs and Van Wyks poems are both politically engaged. Van Wyks poem refers to the democratic right to know. The result? Knowledge is the basis of pain and all evil in verse 3.

“may we give them knowledge

it’s democratic lord,”

The rest of verse 3 and verse 4 refers to nakedness and the knowledge of nakedness like in the story of the Garden of Eden in the left panel in The hay wain. “They” become “us” and a medieval painting is transferred to Afrikaans in the 20th century begging God two times for punishment:

“pluck each other’s fruit

and quickly try to cover up their ardour with begging

hands, leaves and rags, may they have pain,

lord, and together may they collapse

in the dust, punish us thus, lord”

Verses 5 and 6 of the poem is all Hay Wain describing the middle panel.

so it happened that everyone

followed the haywain: the nuns who filled the fat monk’s pockets

with corn, a brother who slit his brother’s

throat, ministers with political commentators

following decently and gluttons perishing under the wheel

a crowd of beasts goading humankind to hell

In principle Van Wyk was (and still is) against all authority and therefor always politically engaged. This becomes clear in verse 8.

every dynast is an antichrist who cares for

his people’s needs

Verse 9 refers to the angel looking up from The Hay Wain followed with a single line as repeated and final statement in verse 10 – a closure – about life on earth between paradise and hell:

because that pain exists is necessary

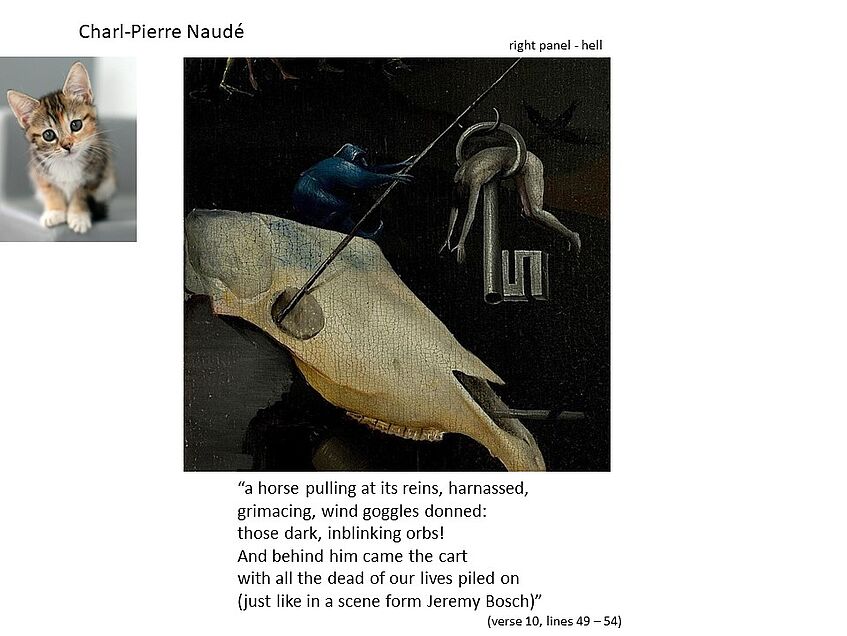

The last and longest poem for this lecture is An animal’s feat from Charl-Pierre Naudé. It is about the death of a cat. Although he didn’t connect this loss only to The Hay Wain, he is aware of the earth rocking implications that vibrate through the empty household. Once more this poem makes a reference to Jung’s concept of synchronicity. It is “meaningful coincidences” that occur with causal relationship between works of different artists. Naudé is aware of it. He announces an apology to Bosch, Chagall and Brueghel in the subtitle of his poem because he transfers his memories to their different paintings. Therefor An animal’s feat is also an ekphrastic poem.

An animal’s feat

(apology to some artists)

Here you can know for sure

I’m talking about a royal creature,

a protector of the gods. One

who would make his visitations

walking on small cushions

through the house of prayer.

Night and day he’d guard

the City Gates of our home

with a doorstopper’s lion heart.

And now?

Where did you go to,

cosmic bud?

We thought you were our prophet in a basket.

Not at all were you the least around here;

you were greater

than anything in the Myths or the Arts.

That tiny fraudster

called shutter speed,

who wink-winks at Darkness

(I’m referring to the calibrated act

of perception),

took mercy on me that day

by granting me to remember my train of observations:

She, distraught animal mistress, stood to one side

in a corner of her high-walled courtyard;

her clothes of mourning dripping wet

from the constant rain.

The grave had been dug, and the coffin waited

for lowering, containing:

three flat candles (no matches, though),

a handful of clovers, a little playing ball;

and wrapped in his life-long blanket:

the corpse of her cat.

(His eyes, always stretched wide –

two round diving watches,

every time he would rise from sleep.)

I am no land tiller – thanks to God –

but, since that day,

my name in the pack

is Jack of Spades.

Thereafter the formalities came hard and fast.

Nothing was omitted,

least of all the hurtful procession;

the black wedding of ground and air –

our little creature heading this up.

Still I see him: the small paws pushed out

from under his funeral blanket,

as if in a brave, headlong march:

a horse pulling at its reins, harnassed,

grimacing, wind goggles donned:

those stark, unblinking orbs!

And behind him came the cart

with all the dead of our lives piled on

(just like in a scene from Jeremy Bosch!)

All our partly, onerously and insatiably

mournable ones

loomed up on this raft of corpses

in front of us.

And our pouring grief, the psyche waters

became unstoppable. Rotten weather (see above).

A threequaters forgotten relative

presented with a hand sticking out

from underneath the fallen ones;

my dad, mom; her father, granddad and a cherished

uncle who seemingly perished in a dream.

Then there was the cousin with fainting deaths;

and my first kiss. Not to mention

the clumsy messenger who fell over in a vision.

Our feline was tiny but an exceptional carter –

pulling all that misery behind him.

Our hearts opened up, and glory, yes

did it come gushing down!

The dead were being pulled with neighing sounds;

wrapped in curtains, from their holes;

and loved ones popped out of the draws

with souvernirs, lucky charms and serviette rings

that had slipped our minds. Also, there was the little fire

that shone in a jewel.

Myself, I just had to recall the blind

whom I had never seen with a single eye;

the unnoticed children flatter than envelopes;

and all that knowledge of the Passion

that furnishes my moral delusions.

And death. Oh, Death. I could see it glimmer

in the side glances

of my tearful mourning, induced no doubt

by hayfever damn it.

Then came the Ascension

of our little animal –

exactly as predicted by the Great Books.

He simply flew up, like an unusual swan.

Last I saw, he had angelic wings

painted on by Marc Chagall.

Anyway, the wagon he pulled gratingly

through the History of Art,

accidently knocked over two toddlers in a Brueghel.

Then it smoothly took to the air,

laden with its freight

of invisible hair.

(There are places in the turns of heaven

that are just like Earth.

How to know? Just listen

to the breaking apart of the urns.)

Meanwhile,

a red wheel came off just above the horizon

and weighed a ton on the Afrikaans side;

then streaked through the sky with a stroke

which rendered the famous chisel break

of the Poet

as a mere dash of paint.

We just stood aghast

with a planet in our chests.

This became lighter as dark descended.

Eventually, as one can expect

from the likes of weather balloons,

we heard that our kitty

(same as you others who so rudely departed

with the lame excuse of death) –

will never return.

But how wrong can one be.

One fine day I walked into a shop,

and there was our fiery saint.

Exhibited on a patch of vilt.

He was glowing in a catch of sunlight,

and roared and raved,

objecting slightly to being held captive

by the oval shape

of a bronze pendant.

Charl-Pierre Naudé

translation: the poet

Naudé describes in verse 1 and 2 the family cat as royalty. It is a pet for kings and prophets and at the same time a dot in the universe. In this homage the body of Naudés cat lays claim to myths and works of art in verse 5. Two famous painters of medieval times become part of this long poem: Bosch in verse 10 and Brueghel in verse 14. In verse 13 Naude jumps to a painter, the Jewish Frenchman Marc Chagall who’s life extended across almost the whole of the 20th century. Jumping or throwing jewelry like a shining string of pearls may be a way this poet works with words in this extended poem. In the last verses the dead recognized cat is in a bronze pendant in a shop.

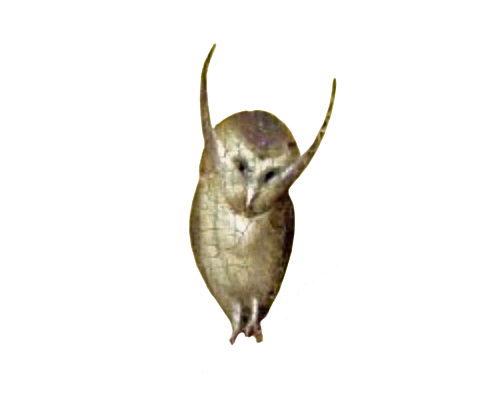

With this shining image I end my little owl lecture here in Vienna. Thank you for your attention.

Bibliography

Breytenbach, B. 2001. Ysterkoei-blues – versamelde gedigte 1964-1975. Kaapstad : Human & Rousseau.

Du Plooy, H. 2014. Die stilte opgeskort. Pretoria : Protea Boekhuis.

Fischer, S. 2016. Jheronimus Bosch - het complete werk. Köln : TASCHEN.

Jarry, A. 1977. Uburleske – UbuRoi, UbuCocu. Amsterdam : Uitgeverij De Bezige Bij.

Jung, C.G. 1976. Synchroniciteit: een acausale, verbondenheid. Rotterdam : Uitgeverij Lemniscaat.

Krog, A. 1970. Dogter van Jefta. Kaapstad : Human & Rousseau.

Dierckx, V. 1572. Pictorum aliquot celebrium Germaniae inferioris effigies. Antwerpen : In de vier winde-uitgeverij.

Louw, N.P. van Wyk. 1959. Ignatius bid vir sy orde : lied vir middelstem en klavier. Kaapstad : Studio Holland.

Louw, W.E.G. 1988. Versamelde gedigte. Kaapstad : Tafelberg-Uitgewers.

Naudé, C-P. 2014. Al die lieflike dade. Kaapstad : Tafelberg-Uitgewers.

Opperman, D.J. 1950. Engel uit die klip. Kaapstad : Tafelberg-Uitgewers.

Shakespeare, W. 2015. Hamlet. London : Penguin Classics.

Shakespeare, W. 2008. Romeo and Juliet. London : Penguin Books.