Learning about the world: developing higher order thinking in music education

J Kruger and L van der Merwe

Abstract

Innovative thinking is an innate human capacity geared towards adaptation and survival. Theories of education accordingly aim at developing teaching-learning strategies that promote creative, problem-solving reasoning referred to as higher order thinking. This essay briefly explains some of the assumptions underlying this concept, and then suggests how they may be reconfigured in a strategy suitable for education in and through music. The strategy involves a basic process of analysis, evaluation and creativity related to actual social experience. Higher order thinking therefore aims to equip learners with the capacity to synthesise relationships in and beyond particular fields of study so that their thinking may expand into the concreteness of the world.

Human history offers an endless vista of resilience and adaptation in the face of frequent cataclysmic natural and social events. The contemporary world accordingly is challenged by violent political uprisings in the Arab-speaking world, economic meltdown in the European Union, piracy along the north-east coast of Africa, the recent birth of the seven billionth human as well as global warming. In South Africa, the quality of drinking water is threatened by irresponsible mining, the poaching of rhinoceros horn seems to spiral out of control, and many poor communities are protesting violently against inadequate government service delivery. These are but a few signs of a world whose disputes continue to require pioneering thinking.

Not all adaptive thinking takes place at international forums. Not so obvious, but arguably no less important, are those daily micro-worlds of children that are ultimately geared towards the unforeseen challenges of their adulthood. The carefully circumscribed settings of school education have come to involve more than the mere transfer of basic knowledge and skills: the need for innovative thinking is a global educational concern, from Japan to Hungary, Sweden and Ireland (Witby et al., 2004:10; Merwin, 2011:122). The National Curriculum of England (2011) as well as the South African National Curriculum Statement (2002) aim to produce learners who are able to identify and solve problems creatively. However, this is not a skill to be developed unreflectively: the latter clearly locates new thinking in social experience by requiring learners to ‘demonstrate understanding of the world as a set of related systems.’

This is echoed in the new South African Curriculum and Assessment Policy Statement (2011) that ‘promotes knowledge in local contexts, while being sensitive to global imperatives.’ Creative Arts specifically aim to ‘develop an awareness of arts across diverse cultures.’

What these objectives allude to is a popular awareness of the socially mediated meanings of art, also a central concern in musicology since the late 20th century. Reacting against the isolationist, product-centred focus of older approaches, new perspectives interrogate the relationship between musicology and ‘the rest of the universe,’ probing its presence on ‘anybody’s list of global priorities’ (Cook & Everist, 1999:xi). In response to this quest, Locke (1999:527) suggests that ‘as classroom teachers and writers we can help shape other people’s views by doing such things as stressing music’s social contexts … [and] by exposing people to musics of other cultures.’

This discussion accordingly explores a way in which we may understand and reflect on the world by means of innovative thinking in music education as well as through music education. We focus on that form of creative problem-solving known as higher order thinking. Our discussion briefly explains certain basic assumptions underlying this concept. It then suggests how these assumptions may be adapted as a strategy in music education. This is followed by a discussion of the kind of teaching-learning content ideally suited to the development of higher order thinking, and illustrated by lesson material dealing with music as lived experience. The strategy then is applied by means of a table that expounds this material in a series of lessons.

Rethinking higher order thinking

Although higher order thinking is a contested concept characterised by diverse definitions and perspectives, it nevertheless is possible to identify certain basic assumptions (Fogarty & McTighe, 1993:162). A key notion is the distinction between reproductive and productive behaviour (Maier, 1933:144) which correlates with so-called lower and higher order thinking. In Bloom’s familiar taxonomy, lower order thinking takes the form of knowledge, comprehension and application, while higher order thinking is manifested as analysis, synthesis and evaluation (Krathwohl, 2002:212).

Perspectives on higher order thinking typically focus on critical, reflective and creative cognitive processes. Creative thinking, as the apex of these processes, is the application of prior knowledge for adaptive purposes (Geertsen, 2003:8; Hanna, 2007:9; Krathwohl, 2002:231; Lewis & Smith, 1993:136). The focus on creative thinking is partly rooted in the revision by Anderson and Krathwohl (2001) of Bloom’s taxonomy, resulting in the following verb hierarchy: remember, understand, apply, analyse, evaluate and create. The essential distinction between the two taxonomies is obviously that, for Bloom, the final stage is ‘evaluate,’ whereas the Anderson-Krathwohl hierarchy culminates in ‘create’ (Hanna, 2007:9), an action that has self-evident, field-specific application in music education.

Useful as the Anderson-Krathwohl taxonomy is for music educators, its generic nature makes little provision for the affective and social qualities of music. Musical thinking self-evidently integrates not merely the affective and the cognitive (Pogonowski, 1987:38), but does so within an embeddedness in social experience (Woodford, 1996:29). Clearly, an approach is called for by means of which these factors may be melded into a useful strategy for developing higher order thinking in music education. To do so we turn to Swanwick’s developmental model for music (1991:155) because of the connections it establishes between four levels, namely musical materials, expression, structure and value.

First, mastery of musical materials entails a sensibility towards these materials as well as an ability to manipulate them. Level two is particularly important because it addresses imitation or ‘expressive character,’ which thus invokes the required affective domain of music. Level three entails structure which, in the simplest sense, refers to recognising structural and textural conventions such as contrast and repetition. The last level is directed towards value, that all-important consideration of music ‘as a form of expression, “embodying, meaning and vision” significant for an individual or community’ (Swanwick, 1988:63, citing Ross). This level links with the pinnacle of a knowledge hierarchy also defined in the AndersonKrathwohl taxonomy, namely metacognition. This is a condition in which humans become aware of and reflect on their thought processes (metacognition is underpinned in the hierarchy by factual, conceptual and procedural knowledge).

Following these specifics of Swanwick’s model, we suggest that higher order thinking in and through music education may be realised when the materials, expression, structures and social values of music are analysed and evaluated, and new music is created accordingly.

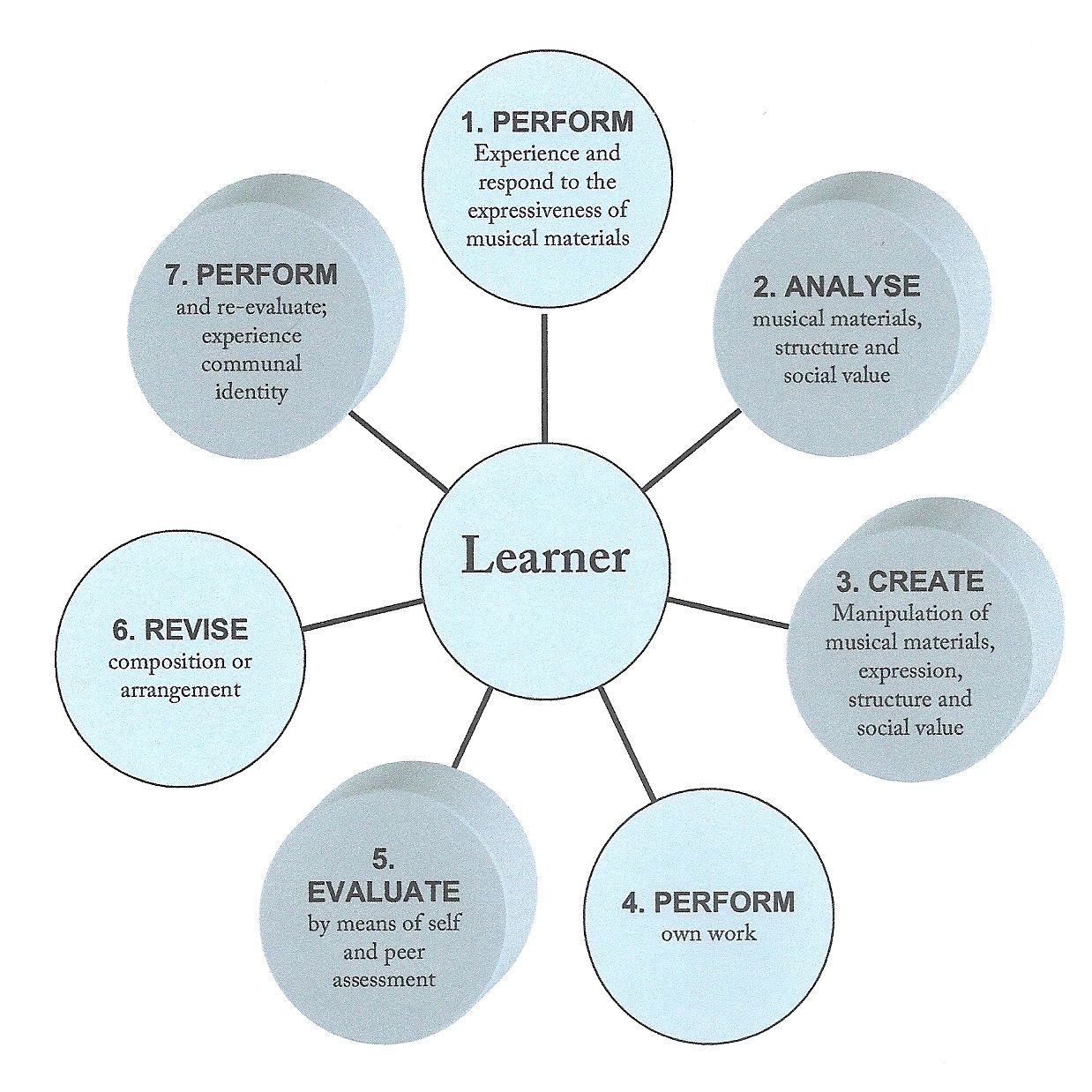

Fig. 1

Strategy for cultivating higher order thinking in music education, synthesised from Anderson and Krathwohl (2002:214), and Swanwick (1991:155)

A strategy for teaching higher order thinking in music education

Like most contemporary teaching models, a strategy for teaching higher order thinking in the music classroom is realised optimally by means of a learner-centered, constructivist approach (Merwin, 2011:123; Sheldon & DeNardo, 2005:41). This approach requires that learners construct meaning for themselves through social interaction, and it accordingly involves strategies such as action learning, cooperative learning and problem-based learning (Fig.1).[1]

The learning sequence in the proposed strategy is as follows: 1) performing existing music, 2) analysing, 3) creating or arranging, 4) performing own music, 5) evaluating own music in terms of existing structures, 6) revising own music, and 7) performing and re-evaluating.

1) Performing existing music

The precondition for higher order thinking is lower order thinking. Lower order thinking in music education takes the form of listening to and performing music. Performance accordingly is considered an application (level 3 in Bloom and Anderson-Krathwohl) of basic musical knowledge and skills (Hanna, 2007:12). The basis of Swanwick’s model (1988) similarly involves sensory response, manipulation of musical materials and mastery of skills. Learners also are required to respond to the expressiveness of the music with movement, dance, singing or instrumental play.[2]

2) Analysing

Knowledge of musical ideas[3] and the social meanings of music may be useful for the creative act. Essentially, learners should be able to identify the elements and socially mediated meanings of music and specify their interrelations (Krathwohl, 2002:231). This process involves differentiation, organisation and attribution, as well as three types of knowledge in the Anderson-Krathwohl taxonomy, namely factual, conceptual and metacognitive. Procedural knowledge (performance) is not involved here.

3) Creating or arranging

Creating is regarded as the most demanding action in the Anderson-Krathwohl taxonomy, requiring critical, problem-solving thinking as well as all the actions in the knowledge hierarchy (remember, understand, apply, analyse, evaluate and create). The creative process comprises three phases through which learners are guided, namely generate, plan and produce (Hanna, 2007:10). Learners are required to apply characteristics of the music they have studied to stimulate their creativity.

4) Performing own music

Performance self-evidently is knowledge in action: it is the expressive manifestation of understanding and acquired skills involving factual (notation), conceptual (principles) and procedural knowledge (skills and techniques) (Hanna, 2007:12).[4]

5) Evaluating own music in terms of existing structures

Evaluation applies the Anderson-Krathwohl knowledge hierarchy in the critical aligning of the work with internal and external criteria (i.e. self and peer assessment). Learners may be assisted in reflecting on their thinking and creativity by means of an analytical rubric (provided by the teacher) of the structures, textures and meanings of the analysed work generated in step two.

6) Revising own music

Evaluation results in revision of creative work, a process identified by Lewis and Smith (1993:134) as a crucial phase in higher order thinking. The teacher provides assistance and monitors the process closely.

7) Performing and reevaluating

The function of a further performance obviously overlaps with that of the initial performance (step four) in that it also requires reflection and assessment. However, it additionally assumes the form of a ritual process[5] that unfolds before and in conjunction with an audience, and as such links expression and values intensely with wider social experience.

Learners are guided to understand that musical products have adaptive, strategic use, and that adjustment to their structure and meanings may be an ongoing process.

Higher order thinking and teaching-learning content: lived experience

A strategy for cultivating higher order thinking in and through music education not only involves a particular learning sequence but also specific requirements in terms of lesson content. Perhaps most important is an awareness of musical meanings, that is, a consideration of creative performance within social settings. It would be entirely possible to analyse musical structures and textures as systems and use the findings to create new music. But this kind of strictly musical problem-solving would not necessarily link with lived experience. Higher order musical thinking in the world therefore requires an awareness of the performative and social qualities of music.

The description of music as social experience that follows accordingly links musical process and product within the context of human migration. There are very few places in the world where tracks made by those fleeing natural disasters, wars, political oppression and economic collapse have not been evident. But of concern here is not so much the reasons for migration, but rather its consequences: although there are many fragments of fact in the images of physical and cultural subjugation portrayed in descriptions of human resettlement, we also have come to understand from the long history of the world that cultural connections routinely are marked by mutual redefinition. Such redefinition in fact involves the essence of what we have come to define as higher order thinking: finding the interface between fields of knowledge by means of some process of analysis, evaluation and the creation of new patterns of existence – patterns that exhibit varying degrees of cultural retention and innovation

The concept of cultural redefinition is explored here by means of an etic category of music we define as ‘songs with wings.’ This concept derives from Nelson Mandela’s description of stories as growing wings and becoming the property of others, ‘enriched by new details and with a new voice’ (preface in Gordon, 2002). The song in question here is Frère Jacques[6] and our discussion deals with its journeys to South Africa and its redefinition in Afrikaans[7] and certain African languages, specifically Tshivenda.[8]

Interaction in colonial South Africa between various European immigrant groups and local populations accounts for the Afrikaans and African versions of Frère Jacques. Although the Portuguese were the first European power to explore the coast of southern Africa (during the late 15th century), it was the Dutch who founded a settlement at the present Cape Town in 1652 to supply their merchant ships with provisions en route to the colony of Batavia (Jakarta, Indonesia). The Dutch remained in control of the Cape until 1795 when it was occupied by the British who, in response to Napoleon’s invasion of the Netherlands, feared that the French might annexe the Cape and therefore threaten their interests in the East. The British returned the Cape to the Dutch in 1803, but, again following French expansionism in Europe, re-occupied the colony in 1806.

While the French therefore effectively were prevented from gaining a colonial foothold in southern Africa, the late 17th and early 18th century nevertheless saw an influx of French immigrants to the Cape, partly as a result of religious conflict in France. These settlers were assimilated into the local population, and their language eventually was supplanted by English, Dutch and Afrikaans.[9]

Most Tshivenda-speaking people of South Africa live in northern Vhembe, a district which borders onto Zimbabwe. Initial contact between them and European immigrants dates back to the first half of the 19th century. Christian missionaries established themselves in the Vhembe area from the middle of the 19th century. Clashes over land led to a short war between Mphephu (a powerful Venda leader of western Vhembe) and the South African Republic in 1898, resulting in the annexation of Vhembe (see Nemudzivhadi, 1985).

The most likely initial means of transfer of songs of European origin to Tshivenda-speakers was the Berlin Mission Society that became active in Vhembe from the 1870s onwards, and whose influence on religious and educational life extended well into the 20th century (see Kirkaldy, 2005). Other forces of cultural influence in the 19th century included migrant labourers who worked in cities like Johannesburg, Kimberley and Durban, as well as the Voortrekkers.[10] Furthermore, Venda adults residing in the Limpopo River basin[11] often tell stories of their incorporation into caring white households as nursemaids and labourers, or as children of labourers who shared in the songs and games of the farmyard (see Figs. 4-6 and 8).

Fig. 2

Fig. 3

Fig. 4

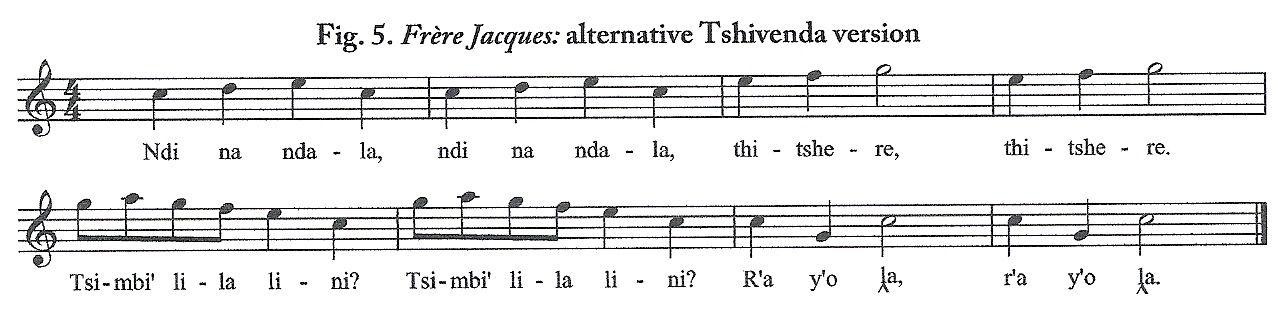

Fig. 5

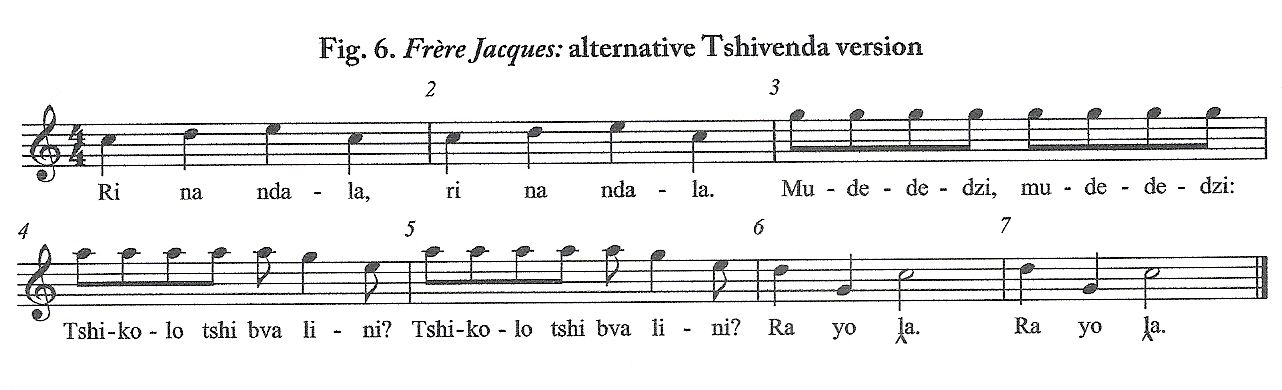

Fig. 6

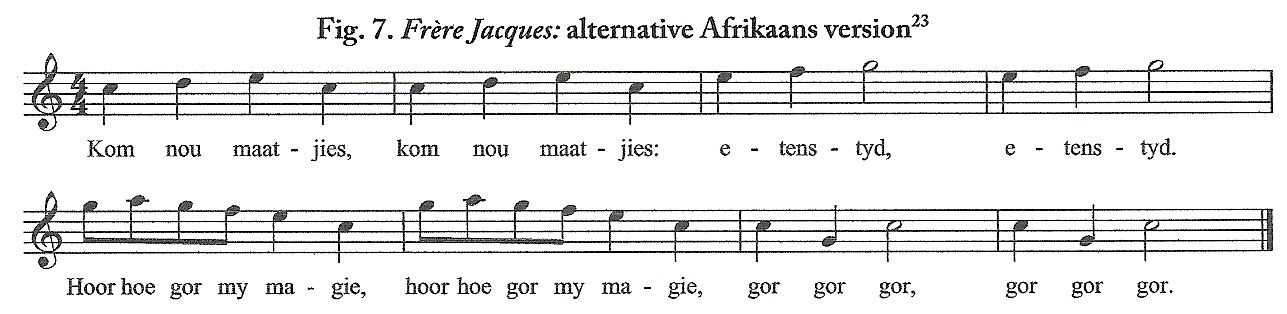

Fig. 7

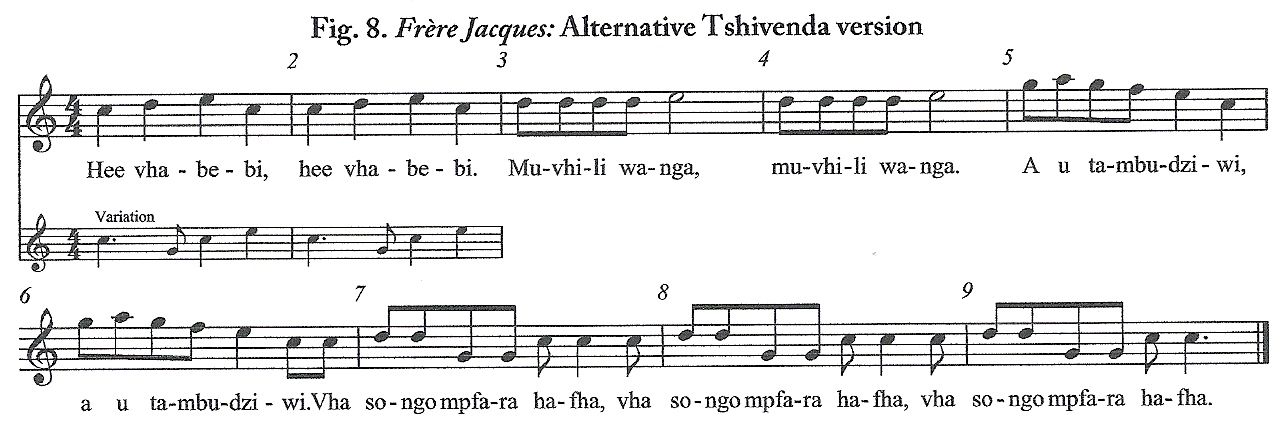

Fig. 8

Plate 1.

Cooks at a feeding scheme, Tshiungani Primary School, Limpopo Valley, 11 June 2009(photo by Jaco Kruger)

Rethinking Frère Jacques: the lyrics

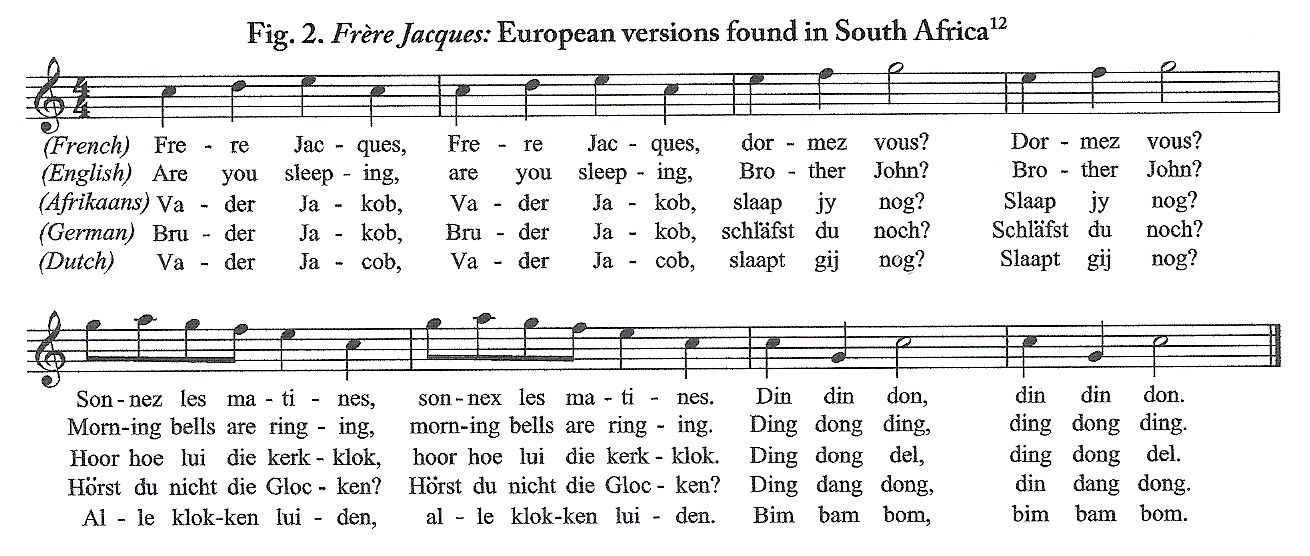

Frère Jacques needs no introduction: it is one of the world’s most beloved and widelyperformed children’s songs. It appears in numerous languages on all continents, as well as in Western classical and popular music. The song has a variety of titles and lyrics, and its meaning and origin is much debated. The most obvious and popularly argued-for explanation points to a religious origin, but it is not known whether the song refers to an actual person. It probably travelled to South Africa with several immigrant groups (Fig. 2).

The popular Afrikaans version of Frère Jacques (Fig. 2) is a faithful reproduction of the standard European form:[13]

Vader Jakob, Vader Jakob, slaap jy nog? Slaap jy nog?

Brother John,[14] Brother John, are you still sleeping? Are you still sleeping?

Hoor hoe lui die kerkklok, hoor hoe lui die kerklok:

Listen to the church bell ringing, listen to the church bell ringing: Ding dong del, ding dong del.

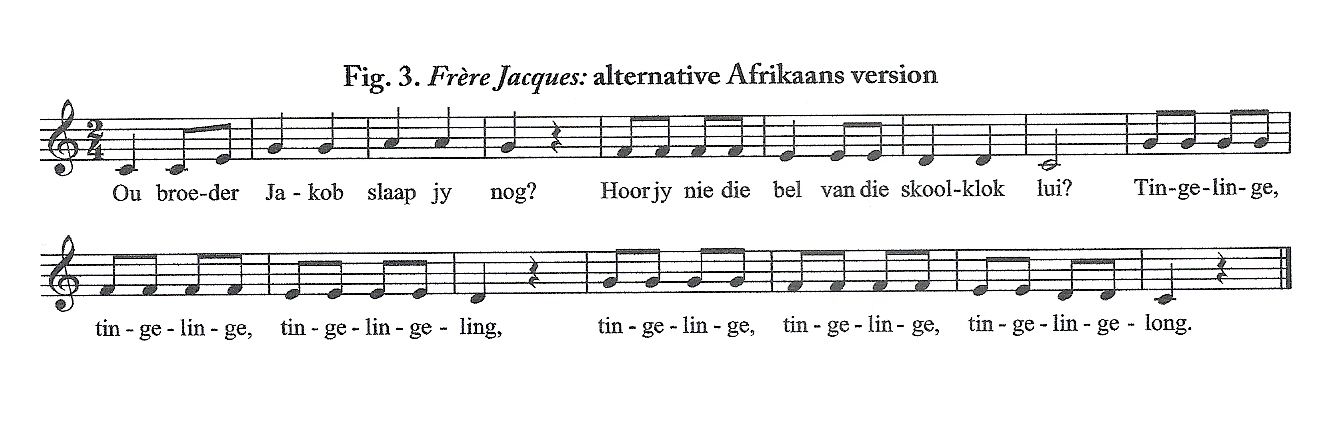

Its variation (Fig. 3), in contrast, retains the image of a bell, but places it within the context of schooling (possibly church schooling, although ‘brother’ obviously is polysemous):

Ou broeder Jacob, slaap jy nog?[15]

Old brother John, are you still sleeping?

Hoor jy nie die bel van die skoolklok lui?

Don’t you hear the school bell ringing?

Tinge-linge-tinge-linge-ling.

Tinge-linge-tinge-linge-long.

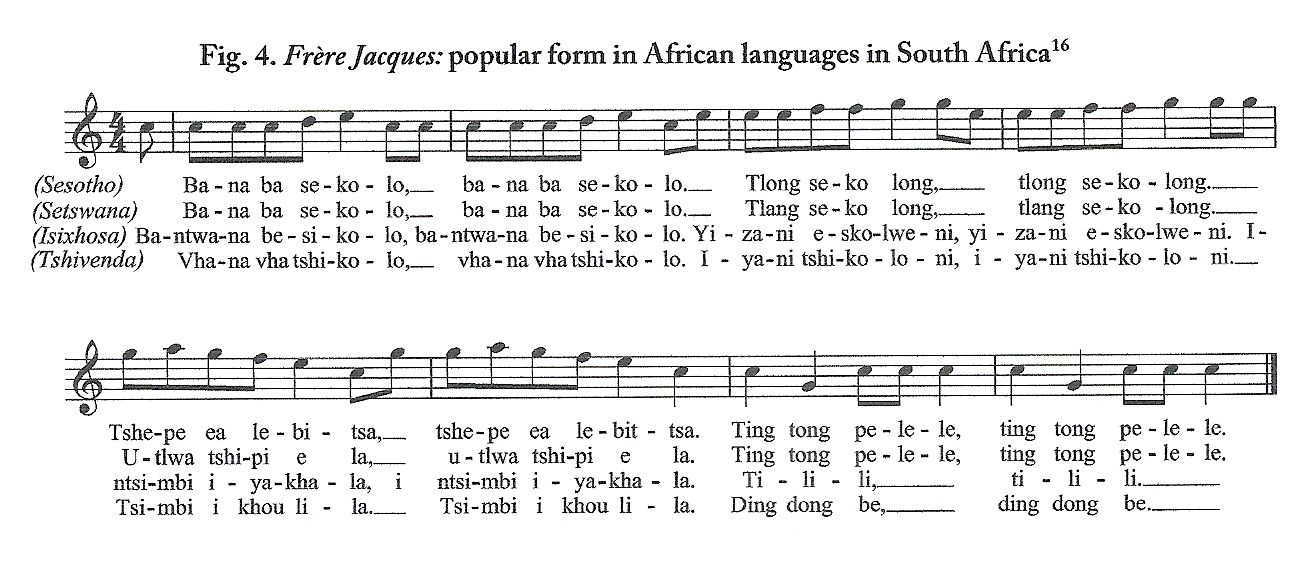

Fig. 3 is not a widely-known contemporary Afrikaans form. However, its lyrics show remarkable correlation with those of a popular redefinition of Frère Jacques in African languages in South Africa (Fig. 4). Church bells of the kind implied in the song are rare in rural South African communities. The majority of local church buildings are modest: they often exist as ordinary community halls or even school classrooms, and do not have bell towers. Hand bells, however, are commonly found at schools, and it is to them that Fig. 4 refers:

Children of the school, children of the school.

Come to school, come to school.

Hear the school bell ringing, hear the school bell ringing.

What may be the oldest and most popular Tshivenda version of Frère Jacques (Fig. 5) retains the original melody but not the lyrics of the European common form. This may be explained by a social setting that expresses new, culture-specific meaning (also see Fig. 6). In precolonial times people rose at day-break and had their main meal of the day during midmorning, between bouts of agricultural and domestic work. It is possible that Fig. 5 originally reflected the adaptation to a different meal schedule brought about by schooling. However, even this older setting has acquired new meaning: settlements on South Africa’s rural periphery are marked by high levels of poverty,[17] and feeding schemes have become widespread at local primary schools (Plate 1). The food learners receive at school often comprises their only daily meal.[18] Figs. 5 and 6 accordingly no longer refer to the school bell but to hunger and eating:

Ndi na ndala, ndi na ndala.[19]

I am hungry, I am hungry.

Thitshere, thitshere.

Teacher, teacher.

Tsimbi i lila lini? Tsimbi i lila lini?

When is the bell ringing? When is the bell ringing?

Ri ya u la, ri ya u la.

We are going to eat, we are going to eat.

Ri na ndala, ri na ndala.[20]

We are hungry, we are hungry.

Mudededzi, mudededzi.

Teacher, teacher.

Tshikolo tshi bva lini? Tshikolo tshi bva lini?

When is school coming out? When is school coming out?

Ri ya u la, ri ya u la.[21]

We are going to eat, we are going to eat.

Fig. 7 is an Afrikaans version whose lyrics suggest experiences similar to those implied in Figs. 5 and 6. Although the song may have been conceived in an older setting of affluence, it links firmly with the emergence of an Afrikaner underclass. There has been a steep increase in unemployment and destitution among Afrikaners over the past two decades. Approximately 10% of them now live below the poverty line and ‘on the fringes of society’ where their racial identity has disadvantaged them severely (O’Reilly, 2010):[22]

Kom nou maatjies, kom nou maatjies: Come on little friends, come on little friends: etenstyd, etenstyd.time to eat, time to eat.Hoor hoe gor my magie, hoor hoe gor my magie:Hear how my little stomach is grumbling, hear how my little stomach is grumbling:gor-gor-gor, gor-gor-gor.grumble-grumble-grumble, grumble-grumble-grumble.

Fig. 8, another Tshivenda version, is a radical if hardly surprising departure from the older meanings of the song. This recent version, with its reference to sexual harassment and abuse, was documented from a preschool teacher,[24] and it plays a role in the teaching of life skills in preschool and primary school. This is not a new educational objective. Tshivenda oral narratives (dzingano) of precolonial origin were told by adults to young children, and they were replete with warnings about the dangers of sexual violation. However, the need for songs like this is related to the fact that dzingano no longer are an integral part of daily existence, gradually having been replaced by the mass electronic media. In addition, the presence of the HIV/Aids pandemic has led to the emergence of music performance categories dedicated exclusively to its prevention.[25]

Hee vhabebi, hee vhabebi!

Hey parents, hey parents!

Muvhili wanga, muvhili wanga.

My body, my body.

A u tambudziwi, a u tambudziwi.

It must not be abused, it must not be abused.[26]

Vha songo mpfara hafha, vha songo mpfara hafha.

Do not touch here, do not touch here.

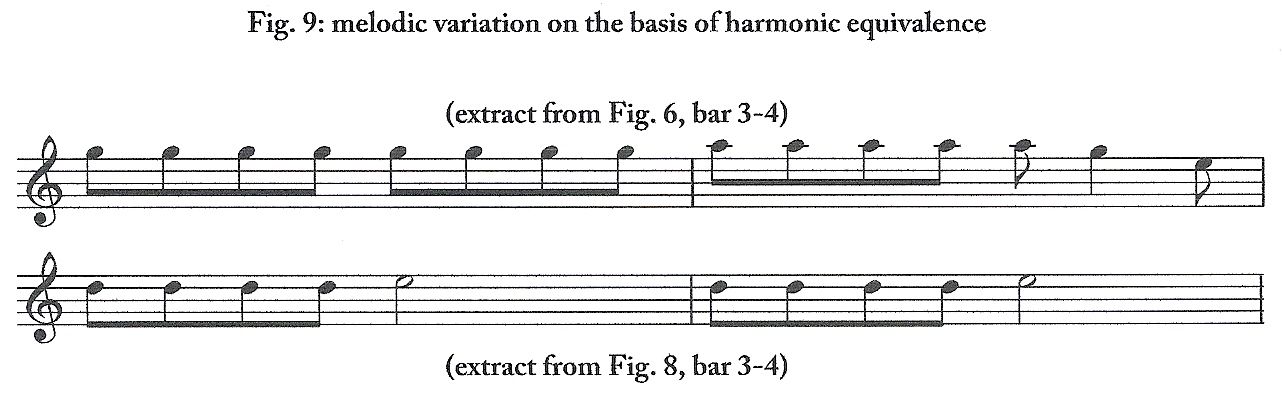

Fig. 9

Rethinking Frère Jacques: the music

With the exception of Fig. 3, all the local redefinitions of Frère Jacques show some stylistic similarity with their European predecessors.[27] There are indications that certain elements of songs with wings generally remain stable, as is evident in the retention of a duple metre in all the local variations of Frère Jacques.[28] Similarly, where the original song is a round, and its variations retain the original melody, the round form also is reproduced (this is the case with Fig. 5; see note 19). However, melodic variations often impede the realisation of round singing.[29]

Melodic variations obviously result from the particular qualities of the language into which a song is recast. This is particularly evident in Fig. 4 in which the melodic contours of the original melody are retained but shorter note values are employed.

The melodic phrase in the first two bars of Figs. 6 and 8 is identical to the original. The final two bars similarly show strong resemblance to the original: the melodic contour is retained but the descending interval is a fifth in both cases, compared to a fourth in the original. This is more than coincidence, and seems to point to features of human memory referred to as the primacy and recency effects, or ‘our tendency to remember the first and last events in a sequence with the greatest accuracy’ (Snyder, 2000:225).[30]

The remaining, central melodic phrases (see Fig. 9), show most deviation. What is significant about them is their harmonic similarity: tones a fourth and fifth apart (in Fig. 9: D-G, D-A and E-A) are considered harmonic equivalents in older forms of Venda music (see Blacking, 1970). Harmonic equivalent tones have the same value: this means that either tone may be used, and that melodies that sound different in fact are essentially identical. This principle is also evident in the melodic variation in Fig. 8 (bars 1-2) in which G in the variation is the harmonic equivalent of D.

To summarise: although a platitude, the redefinition of Frère Jacques underscores a basic cultural practice, namely the embeddedness in changing social experience of the creative integration of old and new lyrics and musical features.

The concepts of expression and social value reflected in the redefinitions of Frère Jacques clearly underscore the importance of the meanings of music and, more specifically, their rootedness in social settings. Cultural redefinition as a theme for exploring higher order musical thinking is particularly useful because it self-referentially also takes the form of such thinking.

All the local forms of Frère Jacques are somehow reminiscent of their European predecessors but none are precise reproductions. While meter remains constant, rhythm and melody show varying degrees of innovation related to linguistic considerations and, to a lesser degree, indigenous musical practice. Lyrics point to shared experiences across social divides: education and poverty are themes that connect most versions. Although change also involves the shedding of some local forms of knowledge, it is clear from Fig. 8 that time-honoured social values are promoted in new cultural forms suited to contemporary experience.

Frère Jacques and higher order thinking in the class room

This discussion integrates the teaching-learning strategy summarised in Fig. 1 with the preceding discussion of Frère Jacques. Each of the seven steps in the teaching-learning process takes the form of a separate lesson, and the entire strategy unfolds in seven lessons. Frère Jacques is only performed in lesson one and analysed in lesson two. It is not the core content of the entire lesson series. After lesson two, the stylistic features and musical ideas from Frère Jacques are used to create and evaluate learners’ own work in lessons three and five.

Although the lessons broadly are conceived for middle to senior primary level, they are not offered primarily as an application on a particular school level, but rather generically to illustrate the application of the teaching-learning strategy.

| Step | Teacher activity | Learner activity | Assessment |

Lesson 1

| Singstwo versions of Frère Jacques in languages most familiar to learners. Encourages learners to create their own movements (including a basic dance step) in response to the different versions. Teaches versions of the song. Shows learners an easy tonic ostinato accompaniment. Asks learners to improve the accompaniment.

| Listens to the songs while performing basic body movements. Responds with different movements to changes and expressiveness in each version. Sings versions of the song. Chooses Orff accompaniment to suit the character of each song. Revises accompaniments.

| Observe each learner’s expressive response to different versions of the song. Observe which learners can play different harmonic progressions on Orff instruments./ Demonstrate melodic contours with hand movements./ Demonstrate rhythmic patterns with different parts of the body.

|

Lesson 2 analyse

| Describes the structure of one version: repetition, contrast, patterns, sequences and variation Guides learners to compare the versions. Initiates a discussion of the value of each version. Discusses group feedback on musical and cultural similarities and differences | Marks the sheet music in different colours to identify the structure of all versions. Groups of four compare the versions and report back. Groups respond to the observations of others. Groups carry out peer assessment.

| Give marks for individual identification of musical structure as indicated in colour on sheet music. Give group mark for comparison.

|

| Lesson 3 create | Instructs learners to create own version of song with personal or local meanings and varied rhythm and melody. Gives learners notated motives which they can choose from. | Creates/notates and explains own arrangement of song (metacognition).

| Assess individual learners for: 1. ability to notate 2. verbal creativity and significance of lyrics creativity in variation

|

Lesson 4 perform | Assists learners at their instruments and with singing own lyrics. | Practises

| Assess melody, rhythm, phrasing and other expressive elements. |

| Lesson 5 evaluate | Monitors and assists groups.

| Carries out self-assessment using the analytical performance rubric (metacognition). Groups do constructive internal peer assessment of each member’s performance in writing. | Use the analytical performance rubric to assess individual performance, manipulation of material, expressiveness, structure and value.

|

| Lesson 6 revise | Assists learners in revising their work based on peer assessment.

| Groups compare individual efforts and develop a group version. Learners may also offer individual versions. | Assess learner response to peer Compare assessments and adjustments. |

| Lesson 7 Perform and evaluate again | Asks learners to reflect on the value of their songs: How does my song relate to my social experiences? What does my song allow me to do? (relates to personal and fellow-feeling and social objectives) | Class selects and motivates their favourite versions of the song. Class performs favourite versions.

| Individuals assess the final version of their own songs. Teacher assesses. final class performances (summative assessment)

|

Conclusion

This discussion posits a strategy for the development of higher order thinking in and through music education. This it does by integrating hierarchies of cognition and knowledge expounded by Anderson and Krathwohl (2001) with Swanwick’s model for music development (1988, 1991).

Nog ´n variasie!! Still another version!!

Prof Jaco Kruger en dr Liesl van Merwe are members of the

School of Music, North-West University, Potchefstroom Campus.

Contact details: Jaco.Kruger@nwu.ac.za

Liesl.Vandermerwe@nwu.ac.za

Notes

[1] The strategy explained here was developed by Liesl van der Merwe with form 3 (grade 9) learners at the International School of South Africa (Mahikeng), following the Cambridge curriculum. These learners had no prior music knowledge. After the strategy had been applied in three lesson series, they were able to perform, analyse, compose and evaluate in the style of the blues, calypso and reggae.

[2] See Bruner’s (2006) three modes of representation that similarly are based on enactive representation (performing a physical task).

[3] In practice this included patterns, sequences, variation, contrast and repetition. These were indicated by means of different colours applied on the sheet music.

[4] Performing in fact involves diverse cognitive skills. It becomes a lower order skill when it involves the application, execution and implementation of basic musical knowledge. However, as a higher order skill it involves the generation, planning and production of new ideas (Hanna, 2007:10).

[5] Ritual process is here identified as an organised gathering characterised by a common focus of attention and the consequent development of shared cognitive and emotional conditions which are a prerequisite for the shaping of identity and creative reflection on social issues (see Collins, 1988:192-197).

[6] Although the song exists in many European languages (see Fig. 2), and here logically should be referred to as ‘Brother John,’ its French title is habitually cited in South Africa.

[7] Although Afrikaans has Germanic roots, it evolved in colonial South Africa as a new vernacular generally not intelligible to speakers of Germanic languages.

[8] Tshivenda is one of South Africa’s minority indigenous languages, and it is spoken by just more than a million people, or some two percent of the total population (see www.statssa.gov.za).

[9] The French influence in South Africa is still evident, amongst other legacies, in the winemaking industry, architecture and the abundant presence of French first names and surnames, mostly among Afrikaans-speaking descendants of Dutch immigrants.

[10] Settlers who moved away from the Cape, partly to escape British control.

[11] Low-lying areas adjoining the Limpopo River along its course on the boundaries between Botswana, Zimbabwe, South Africa and Mocambique. This swathe has a rural population of about 14 million people. The local area inhabited by Tshivenda-speakers is situated between the Soutpansberg and the Limpopo River, and it is called Niani. It was occupied by white farmers following the Land Act of 1936, particularly after World War Two. Most displaced residents became farm or migrant labourers.

[12] See www.ingeb.org/Lieder/bruderja.The keys in which transcriptions are presented have been selected for purposes of presentation and not performance.

[13] Its lyrics most closely resemble the German version.

[14] It is not clear why the English version of the song mostly refers to John, while the French, German and Dutch versions refer to the equivalent of James.

[15] Jo Fourie collection, 315/160 (South African National Archive).

[16] The Setswana, Sesotho and Isixhosa lyrics were provided by Rigardt Pretorius, Eddie Mofokeng and Yvonne Myeki respectively (Potchefstroom, North-West University, 7 March, 2011). The Tshivenda lyrics were documented from Asinathi Nenzhelele, Folovhodwe, Vhembe district, 16 June, 2011.

[17] There are conflicting estimates of the unemployment rate in the Vhembe district, ranging from the national average of 25% to as high as 65% (www.vhembe.gov.za /docs/Local%20 Economic%20analysis.pdf). Rural (and many urban) settlements generally lack adequate infrastructure and employment opportunities. Numerous families rely heavily on welfare grants, pensions, migrant labour remittances and state-sponsored housing.

[18] Local cooks are contracted to provide meals, and in the area where Fig. 6 was documented (Niani; see note 11), the menu usually consists of a very limited variety of local produce, especially leafy vegetables (muroho), cabbage and beans, in addition to the staple, maize porridge.

[19] Performed in round form by Mashudu Mulaudzi, with Judith and Florence Mamarigela, Tsianda, 4 July 1988.

[20] Performed by Joseph Mabuli, Masea, 11 June 2009.

[21] The correct orthography of la (eat) cannot be reproduced here, but appears in the song transcription.

[22] Also see www.newint.org/columns/essays/2010/01/01/afrikaners-hit-bottom/ 23 Ria Raath, Potchefstroom, 8 March 2011.

[23] Gloria Ndwamato, Folovhodwe, 27 September 2010.

[24] As is evident in preschool and primary school songs, school dramas and the special category of HIV/Aids songs in the national South African Schools Choral Eisteddfod.

[25] Lit. it must not be played with.

[26] Although Fig. 3 therefore is unique, it nevertheless is reminiscent of another familiar European song, namely Ah, vous dirai-je, maman (‘Twinkle, twinkle little star’).

[27] The South African derivations of ‘Three blind mice’ and ‘Oranges and lemons’ similarly retain the original metre.

[28] Although Venda musicians are quite capable of singing in round form, there is no evidence of such singing in older musical categories, and this is presumably why it is only rarely apparent in contemporary school music performance.

[29] Clearly then, not all stylistic traits in redefined music are the result of conscious choice. For further discussion see Kruger (2006).

Bibliography

Anderson, L.W., & Krathwohl, D.R., eds. 2001. A taxonomy for learning, teaching, and assessing: A revision of Bloom’s taxonomy of educational objectives. Abridged. NewYork: Longman.

Blacking, J. 1970. Tonal organisation in the music of two Venda initiation schools.Ethnomusicology, 14(1):1-54.

Bruner, J.S. 2006. In search of pedagogy: the selected works of Jerome S. Bruner. London:Routledge.

Collins, R. 1988. Theoretical sociology. San Diego: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich.

Cook, C. & Everist, M., eds. 1999. Rethinking music. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Fogarty, R & McTighe, J. 1993. Educating teachers for higher order thinking: the threestoryintellect. Theory into practice, 32(3):161-169.

Fourie, Jo. Collection of Afrikaans folk songs. Pretoria: South African National Archive.

Geertsen, H.R. 2003. Rethinking thinking about higher-level thinking. Teaching Sociology, 31(1):1-19.

Gordon, M., ed. 2002. Madiba magic: Nelson Mandela’s favourite stories for children. Cape Town: Tafelberg.

Hanna, W., 2007. The new Bloom's taxonomy: implications for music education. Arts Education Policy Review, 108(4):7-16.

Kirkaldy, A. 2005. Capturing the soul: the Vhavenda and the missionaries. Pretoria: Protea.

Krathwohl, D.R. 2002. A revision of Bloom's taxonomy: an overview. Theory into practice, 41(4):212.

Kruger, J. 2006. Tracks of the mouse: tonal reinterpretation in Venda guitar songs. (In Reily, S.A., ed. The musical human: rethinking John Blacking’s ethnomusicology in the 21st century. Aldershot: Ashgate. p. 37-70.)

Lewis, A. & Smith, D. 1993. Defining higher order thinking, Theory Into Practice, 32(3): 131.

Locke, R.P. 1999. Musicology and/as social concern. (In Cooke, N. & Everist, M., eds., 499-530).

Maier, N. R. F. 1933. An aspect of human reasoning. British Journal of Psychology, 24:144–155.

Kruger & Van der Merwe 80

Merwin, W.C. 2011. Models for Problem Solving. The High School Journal, 61(3): 122-130.

National Curriculum of England. 2011 curriculum.qcda.gov.uk/uploads/ Curriculum %20aims_tcm8-15741.pdf

Nemudzivhadi, H. M. 1985. When and what: an introduction to the evolution of the history of Venda. Thohoyandou: Office of the President.

O’Reilly, F. 2010. Poverty within White South Africa. www.

boston.com/bigpicture/2010/07/poverty_within_white_south_ afr.html

Pogonowski, L. 1987. Developing Skills in Critical Thinking and Problem Solving. Music Educators Journal, 73(6):37-41.

Sheldon, D.A., & Denardo, G. 2005. Comparisons of higher-order thinking skills among prospective freshmen and upper-level preservice music education majors. Journal of Research in Music Education, 53(1):40-50.

Snyder, B. 2000. Music and memory: an introduction. Cambridge, Massachusetts: The MIT Press.

South African Curriculum And Assessment Policy Statement. 2011. Life skills grade 4-6. Pretoria: Department of Education.

South African National Curriculum Statement. 2002. Revised National Curriculum Statement Grades R-9 (Schools) Arts and Culture. Pretoria: Department of Education.

Swanwick, K. 1988. Music, mind, and education. London: Routledge.

Swanwick, K. 1991. Music curriculum development and the concept of features. Journal of Aesthetic Education, 25(3):147-162.

Witby, K., Taggart, G. & Sharp, C. 2004. International review of curriculum and assessment frameworks curriculum and progression in the arts: an international study: final report. London: National Foundation for Educational Research.

Woodford, P. 1996. Developing critical thinkers in music. Music Educators Journal, 83(1):27-32.

Interviews

Mabuli, J. Masea, Vhembe district: 11 June 2009.

Mofokeng, E. North-West University, Potchefstroom: 7 March, 2011.

Mulaudzi, M., Mamarigela, J. & Mamarigela F. Tsianda, Vhembe district: 4 July 1988.

Myeki, Y. North-West University, Potchefstroom: 7 March, 2011.

Ndwamato, G. Folovhodwe, Vhembe district: 27 September 2010.

Nenzhelele, A. Folovhodwe, Vhembe district, 16 June, 2011.

Pretorius, R. North-West University, Potchefstroom: 7 March, 2011.

Raath, R. Potchefstroom: 8 March 2011.

Gepubliseer: Afrikaans in Europa Augustus 2014

© Catharina Loader 2001